Lighting the Way: Effective Use of Lights and Sights in Law Enforcement Operations

What to Know

- Proper low-light training should cover principles of light use, equipment considerations, and tactical decision-making to improve officer safety.

- Understanding the differences between mechanical sights and red dot sights (RDS) is crucial when using various lighting and sighting systems in low-light conditions.

- Training must include how to switch between primary and backup lights, and when to appropriately use weapon-mounted lights versus handheld lights.

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” – Desiderius Erasmus

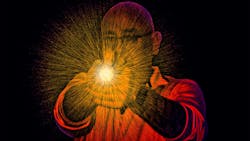

That reality will never change although there are some folks who would suggest that in such circumstance the one-eyed man would be considered a freak and an outcast simply due to his empowering difference. Set that odd thought aside for a minute and realize the concept can be applied almost equally to no-light situations. “In a conflict in the dark, the man who controls the light is king.”

Further reality is that roughly 80% of law enforcement use of force decisions are made in low- or no-light situations. These are the situations wherein we bring our own light and, if we’ve been trained properly, use it to our best advantage. “Trained properly” are the key words in that sentence and part of what this article focuses on.

Twenty-five years ago, training with a flashlight meant learning how to hold it while you were shooting and how to search with it without making a target of yourself. Any officer in the business long enough to remember the training back then remembers the “FBI technique” of holding the light away from your body at arm’s length. Why? Because bad guys shoot what they can see and, in the dark, they’d likely shoot at the light. I’d like those incoming rounds to be as far from my body as possible, so that light needed to be as far as I could reach out away from my torso.

Low-light training today should include:

- Principles and tactics of using a flashlight to the officer’s optimal advantage in low-light conditions.

- The difference between mechanical sights and RDS while using a flashlight, whether mounted or not.

- Techniques for switching from primary to secondary (backup) lights if the primary fails or ergonomics demand.

- Appropriate circumstance for using the weapon-mounted light for anything other than immediate engagement.

- Concerns and considerations for officer survival and high risk tactics when using a weapon-mounted light.

- The differences between on-duty and off-duty with a weapon-mounted light (if you think there’s no difference because “cops are always on duty,” consider your holster and concealment while off-duty).

- Light control while working individually and within a team.

- Battery management

Then we entered the age of weapon-mounted lights becoming far more common and the training largely focused on manipulating the light while on the range. Turn it on, engage your target, turn it off. There might have been some classroom training about agency policy, what types of lights were approved, holster security mandates and perhaps a few other administrative items. How many of you reading this ever heard, “Remember that if the light is on the gun and the sights are lined up with your shooting eye, the light is in front of your face and there’s a strong chance that’s where the incoming rounds will go, so unless you want to get shot in the face, DON’T use the weapon-mounted light unless you have to?”

As a veteran patrol officer, firearms instructor, SWAT cop and low-light instructor, I have to admit that I’ve never been a fan of pistol-mounted lights except for two assignments: SWAT and K-9. Why those two? Because we humans only have two hands. For SWAT and K-9 there’s a good chance your off hand will have something in it - a shield or a leash - and you might need the light on your gun simply because you don’t have a hand free to hold it AND the gun. But the 18,000-plus agency leaders in this country didn’t ask my opinion and Hollywood, via TV and movies, absolutely glorified weapon-mounted lights. So, somewhere in that 20-25 years ago time frame, we started seeing agencies approve pistol-mounted lights and most of them were smart enough to mandate training to accompany the new policies. However, the training was firearms only, at the range, and really only involved manipulating the light while identifying and engaging targets.

That isn’t low-light training. That’s low-light firearms qualification. True low-light training involves information on the lights in general, measuring light (the age old debate between candlepower, lumens and candela), how much light is enough and how much may be too much, proper deployment and control of the light, battery management and more. The single most powerful statement I ever heard in training and one I haven’t heard very much since was, “See from the opposite perspective.” All too often we are our own worst enemies because we either over-use or poorly control the light.

But, welcome to 2026 where most law enforcement pistols, in the big cities anyway, are quickly becoming weapon systems rather than (simply) duty sidearms. Not only do agency duty weapons have lights on them but optics as well, and I can’t help wondering how much training has gone into the considerations of red dot sights (RDS) in low-light conditions?

When developing training for low-light operations, at its most basic, the training should cover how to perform when any piece of equipment fails. Sure, it’s easy to train officers on how to search a structure using a light. But teaching judgmental use of force with a firearm is different when you consider the myriad possibilities of mechanical sights, RDS, weapon-mounted light, handheld light, projected laser dot sights and more. And let’s ask another question as well: if circumstances don’t support searching with their weapon presented, should they be using a weapon mounted light to perform the search?

Take a look at the list and consider whether or not it’s all covered in your agency’s training on low-light tactics, or the use of weapon-mounted lights. All too often, we add new tools and capabilities without proper administrative or training support for the same. If your agency authorizes but doesn’t provide a weapon-mounted light, what are the controls for the type of light? Who pays for the holster, and what are the design requirements for it? Is the additional training required prior to mounting the light? Are there any controls on your weapon-mounted lights for an off-duty weapon? (This question most especially applies if your off-duty weapon is different from your issued duty weapon.)

Weapon-mounted duty lights have become widely accepted today, but that doesn’t mean that the use of them is being adopted and enacted properly. Make sure you do it right and pass any concerns you have up your chain of command.

Low-light training today should include:

- Principles and tactics of using a flashlight to the officer’s optimal advantage in low-light conditions.

- The difference between mechanical sights and RDS while using a flashlight, whether mounted or not.

- Techniques for switching from primary to secondary (backup) lights if the primary fails or ergonomics demand.

- Appropriate circumstance for using the weapon-mounted light for anything other than immediate engagement.

- Concerns and considerations for officer survival and high risk tactics when using a weapon-mounted light.

- The differences between on-duty and off-duty with a weapon-mounted light (if you think there’s no difference because “cops are always on duty,” consider your holster and concealment while off-duty).

- Light control while working individually and within a team.

- Battery management.

About the Author

Lt. Frank Borelli (ret), Editorial Director

Editorial Director

Lt. Frank Borelli is the Editorial Director for the Officer Media Group. Frank brings 25+ years of writing and editing experience in addition to 40 years of law enforcement operations, administration and training experience to the team.

Frank has had numerous books published which are available on Amazon.com and other major retail outlets.

If you have any comments or questions, you can contact him via email at [email protected].