The outrage was predictable. It always is. So was the offended counterpunching and self-righteous (and self-serving) return fire that, frankly, completely missed the point and any opportunity to feel or show empathy, offer understanding, or even create a teaching moment. Facebook was the platform, of course, and the events the type of hot button topics that too often push division over dialogue, and fuel the growing sense of constant “us vs them-ism” infecting social media.

The latter half of April 2018 was notable – or notorious, depending on your outlook – for a number of high profile events. Perhaps first among them, at least on a national level, were the protests and walkouts planned and carried out coast-to-coast by high school students in the wake of the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL. A sweeping call for gun law reform, the protests, walkouts, and a number of prominent student leaders who have taken center stage became the focus of rancorous debate, largely played out on Facebook and Twitter. It was a movement that launched (as many movements do these days) a thousand and one memes in support of, and opposition to, the movement.

And then came the pushback from the law enforcement circle, and not really to the idea of gun law reform so much, but rather in the form of critical “butwhataboutisms… .”

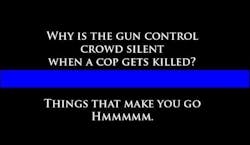

Specifically, and almost certainly in response to another notable trend media savvy cops were more than aware of: Through the end of April 2018, there were 30 line of duty deaths related to felonious assault occurring in 2018, and three LOD deaths directly related to health issues stemming from the aftermath of 9/11. So, in response to the flood of memes all across social media about and in support of the high school protests, certain others from the community of law enforcement and its supporters sprang up, along the lines of the one shown above in the photo carousel.

Brief and on point, seemingly eloquent, and certainly galvanizing, but is it fair to, or at all reflective of, the attitudes or focus of those who advocate for stronger gun laws? A lot of LEOs and LE supporters seemed to think so wherever it (or something similar) popped up, deeming a lack of public outcry over LOD deaths as hypocrisy, or clearly assuming a correlation about others’ beliefs about gun control and the meaning of the Second Amendment with their perceived views of law enforcement. Realistically, though, that seems a rather narcissistic reading of something that really has nothing at all to do with law enforcement or police officers in general, or any specific officer in particular.

For a platform conceptualized to unite and bring people together, social media is as much a wedge of divisiveness and acrimony. This is not to say we are not consumers of social media ourselves, or advocates and utilizers of its powerful cohesiveness. But we are very familiar with the psychological dangers that arise when powerful technology, continuously advancing at a rate that tests our collective capacity to keep pace with intellectually and emotionally, runs into a sometimes primitive human nature evolved to detect and respond to danger and threats with anxiety, defensiveness, and a choice of either withdrawal or attack.

The psychological dangers of social media

For all its benefits and potential, social media is capable of driving anger and disequilibrium, shaking our sense of wellbeing and trust, and, for many, fostering a sense of constantly being on guard to fend off challenging and even dangerous-sounding ideas. Until relatively recently most of us lived and operated in a world of relative intellectual comfort, in self-selected, mutually supportive community with a largely homogenous social circle made up of family and friends. We knew there were different ideas and opinions than our own, and generally accepted them in theory, but rarely in history have the realities of such widespread diversity of thought been so in our face, or so constantly. When that diversity takes aim at our core beliefs, throwing roundhouses at the very foundations of our identity, we take it personally.

Often the anger and disequilibrium comes from our personalization of these core belief challenges, viewing them through a narrow lens of our own creation rather than considering the views and experience of others, or overestimating our own importance in the eyes of someone else. For the LEOs and LE supporters who somehow personalized widespread anti-violence/pro-gun control protests as an attack on law enforcement or ignoring the deaths and concerns of fallen officers and the ones they leave behind, it is a combination of these three factors. The danger of this personalization is how easily and commonly it leads to resentment, distrust, and social isolation.

Understanding outside points-of-view (and how they’re really not about you)

Take the meme example, and the thought distortion that widespread silence about LOD deaths among those protesting gun violence somehow implies indifference or even approval of violence against officers. In order to de-personalize it is important to understand how the concept of Communities of Identification and Interest influence social media community self-selection and the algorithms that support it. First, silence is not so widespread as many in the law enforcement community believed, as I was able to see many comments and expressions of support for law enforcement losses from those in the stricter gun laws/control camp and, second, as I posted in reply to someone who believed in the “pro-gun control = anti-law enforcement” equation:

…as to "why are they silent?", it's being overthought. The simple answer is probably that the vast majority are unaware of police LOD deaths on social media, and what awareness they do have cycles through local news feeds only. I (a police officer) am mostly unaware of fire service LOD deaths and injuries because I pay no attention to the fire service on social media, and am not privy to localized stories. If you don't select to pay attention, or have direct connection to others who do, what you see is heavily filtered to your preferences. For instance, I have friends in different professions who pay close attention to sites specific to their professional interest(s), and are friends with others who do, as well. They live a very different online world than I do, except where we share common interests, and I'll only ever see snippets of their other life if/when they choose to post it. Likewise, my *other* professional life in social work leads me to see and respond to things my LE friends will be ignorant of unless I choose to publicly share information. It is less about lack of interest or concern and has everything to do with social media algorithms. Frankly, before widespread social media use most cops were no more privy to localized stories about LOD deaths 800 miles away than were the rest of the public outside of reading occasional published stats.

Simply, we choose our communities both online and off, and the choices we make dictates what we see and are aware of, choose to think and care about, and share with others through memes (defines as idea(s), behavior(s), or style(s) that spread from person to person within a culture—often with the aim of conveying a particular representational phenomena, theme, or meaning – adapted from Mirriam-Webster), and now particularly internet memes. We self-select – and separate – and how we do so determines what we see and know.

Coming back to center (finding your equilibrium)

As always, finding perspective is critical to avoid unnecessarily traveling dark roads of the mind. Learning to consider the point-of-view of others with curiosity and empathy, even when you may disagree, is revealing, and what it reveals is how few of their thoughts are about you at all! Finding perspective is a choice that constantly needs to be made, but the effort is well worth it.

In our next article we will continue exploring how we can reshape how we think and react to an often seemingly hostile world.

About the Author

Michael Wasilewski

Althea Olson, LCSW and Mike Wasilewski, MSW have been married since 1994. Mike works full-time as a police officer for a large suburban Chicago agency while Althea is a social worker in private practice in Joliet & Naperville, IL. They have been popular contributors of Officer.com since 2007 writing on a wide range of topics to include officer wellness, relationships, mental health, morale, and ethics. Their writing led to them developing More Than A Cop, and traveling the country as trainers teaching “survival skills off the street.” They can be contacted at [email protected] and can be followed on Facebook or Twitter at More Than A Cop, or check out their website www.MoreThanACop.com.

Althea Olson

Althea Olson, LCSW and Mike Wasilewski, MSW have been married since 1994. Mike works full-time as a police officer for a large suburban Chicago agency while Althea is a social worker in private practice in Joliet & Naperville, IL. They have been popular contributors of Officer.com since 2007 writing on a wide range of topics to include officer wellness, relationships, mental health, morale, and ethics. Their writing led to them developing More Than A Cop, and traveling the country as trainers teaching “survival skills off the street.” They can be contacted at [email protected] and can be followed on Facebook or Twitter at More Than A Cop, or check out their website www.MoreThanACop.com.