Memorial Reconnects Slain Deputy's Relatives

TAMPA — The brutal murder of a Hillsborough County sheriff’s deputy seven decades ago is bringing together cousins from across the country who never knew of one another before.

The occasion is the dedication Thursday in Tampa of a memorial to 15 local deputies known to have died in the line of duty.

One of those deputies, whose story was largely a mystery to the sheriff’s office until recently, is Robert Maxwell Suarez — stabbed 17 times and shot to death while serving civil papers over an unpaid furniture bill on Sept. 22, 1944.

“This is exciting,” said Sandra Gonzalez, 68, who until September had never heard of Suarez and now looks forward to meeting his son and her first cousin, William Suarez, 73. “But it’s still a little bit hard to believe I have long lost family. It’s surreal.”

A researcher contacted Gonzalez while trying to track down relatives of Suarez through his obituary in the Tampa Tribune.

Gonzalez told the researcher he had the wrong number.

Then she was read the names of eight surviving siblings in the Suarez obituary and recognized the names of her mother, four uncles and one aunt. Still, Gonzalez was skeptical because the other two siblings were unfamiliar to her.

Still working from the obituary, the researcher contacted Suarez’s two surviving children, William Suarez of Dunnellon and Carole McEwen, 78, of South Carolina.

They also dismissed the connection to their father, saying they had never heard of the six siblings.

Their father had only one full sister and, through his mother’s second marriage, a half-brother, they insisted.

Genealogists brought in to help in the research came to a different conclusion.

“Information for obituaries is provided by a member of the family,” said Drew Smith, president of the Florida Genealogical Society. “Listed names are pretty accurate. People may be omitted, but rarely added accidentally.”

Tampa historian Dad Perez also helped in the search and confirmed that the obituary was correct.?

?

The children of Deputy Suarez are related to Sandra Gonzalez through their grandfather, Jose Suarez.

Jose Suarez was married twice; the son who became a deputy was born into his first marriage and Gonzalez’s mother was born into the second one.

The two families lost contact at some point for reasons that may never be known.

Sandra Gonzalez and William Suarez first spoke by phone in September and made plans to restore contact between their families during the dedication of the memorial in May.

Carole McEwen, the deputy’s daughter, lived long enough to learn about her lost cousins but was too ill from cancer to speak with Sandra Gonzalez. McEwen died in October.

Her husband, Roy McEwen, hopes to make the trip to Tampa this week.

Also attending the dedication will be Zolia Rodriguez, another daughter of a sibling of Deputy Suarez from the second marriage.

William Suarez is bringing all three of his sons.

“I can’t wait to meet everyone,” Sandra Gonzalez said. “Hopefully we can begin a relationship between our families that lasts. I’d love to learn more about my uncle.”

That may be a tall order.

Suarez has long been a mystery to the sheriff’s office. Besides the way he died, little was known about him.

The histories of many fallen officers from decades past are shrouded in mystery. Even the month and day remains unknown for Deputy Richard Roach, and there is no photo of him.

Instead, a photo of a sheriff’s page appears next to Roach’s name in the memorial at the new Fallen Heroes Remembrance Park, at Eighth Avenue and 19th Street. The memorial consists of a large sheriff’s office badge in mosaic tile as the floor, a statue of a sheriff’s honor guard and a granite wall with glass panels containing the name and photo of each deputy.

?

Roach died in 1874 when Tampa was a small town with dirt roads. Proper record keeping was years away.

They were lacking even in the mid-1900s when Robert Suarez was slain.

“Record keeping existed when Deputy Suarez was killed, but it was not the same as today,” said Master Deputy Jerry Carey of the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office. “So we rely on the family of the fallen deputies from those earlier eras. But in those days a lot of times tragic things would happen and people had a tendency to grieve and move on.”

In the case of Suarez, the man he was serving papers on refused to accept them, according to what records remain of the incident.

A scuffle broke out.

A knife was thrust into Suarez’s head 17 times. He was then shot in the abdomen and shoulder.

The next day, the father of four died from his injuries.

Like his parents, Suarez had children from two marriages.

His first wife, Lois Carter Moore, was a respected musician.

They married in 1929, had two children — Robert Jr. in 1931 and Carole in 1935 — then divorced in 1940.

Suarez later married Elizabeth Barr. Their son William was born in 1942 and daughter Patricia Ann in 1945 — after Suarez’s death.

Only Robert Jr. was old enough to have lasting memories of his father, but he died two years later in 1946.

In an interview before her death, daughter Carole McEwen said she never learned how her father died until she reached adulthood. Her mother never wanted her to know. She never even mentioned Suarez.

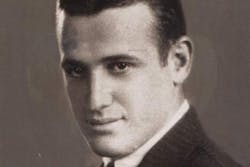

Said McEwen, “My mom and dad divorced when I was 5 and I only saw him on weekends after that. All I remember is going to the beach with him. And of course I can’t forget how handsome he was.”

?

With chiseled Latin looks and thick jet black hair, he looked more like a movie star than a deputy, McEwen said.

Some information on Suarez is provided through city archives and census reports.

He was born in Tampa on June 8, 1904.

Before joining the sheriff’s office, Suarez sold cars, worked in a pet shop and owned Nance-Suarez Poultry with Leonard Nance, considered one of the early pioneers of baseball parks in Tampa.

“That’s more than I knew,” McEwen said, when informed of her father’s history. “I didn’t have my father’s family around to tell me anything.”

McEwen said her father’s sister Carmen moved to Davis Islands in Tampa for a short period after the murder but she saw little of her. Her aunt returned to New York City, where she had lived for years.

Neither McEwen nor William had a relationship with their paternal grandparents before or after their father died. They wondered whether there was a rift.

According census reports, Jose Suarez, the deputy’s father, was from Spain, worked in the tobacco industry and regularly traveled between Tampa and Cuba in the early 1900s.

Perhaps it was to purchase tobacco. Or perhaps it was to visit Suarez’s mother, who was from Cuba and not living in Tampa at the time.

Jose divorced and remarried, then settled in Tampa in 1908. His second wife gave birth to six children — Jose Jr., Mercedes, Carlos, Rosa, Manuel and Geronimo.

Suarez’s mother also settled in Tampa, married a man named Garcia and gave birth to one son, Angel Garcia, whom McEwen met on several occasions as an adult.

Though both his parents and many siblings lived in Tampa, Robert Suarez was raised by an aunt.

“That’s sad,” Sandra Gonzalez said. “He must have been lonely.”

Grandfather Jose passed away in 1946.

“Families are not always like ‘Leave It To Beaver,’” said Smith, with the Florida Genealogical Society. “When the complicated part of the family’s history takes place in the early 1900s and crosses into other countries, it gets even more confusing, and that’s how family can be lost.”

“Children from a first marriage may fall out of touch with family of a second marriage,” added Perez, the historian. “After 40 or 50 years, they can easily be forgotten. When you add divorces and remarriages to the mix, information often gets suppressed and never discussed or shared across families.”

McEwen’s husband Roy said his wife and her brother William also were estranged for 40 years, losing touch after they moved from Tampa.

They reconnected about 10 years ago, Roy McEwen said.

“It was a very emotional day,” he said. “I’d expect this reunion of cousins to have some emotions too.”

2014 the Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Fla.)

McClatchy-Tribune News Service