How to Catch A Criminal: Every Silver Lining Has a Cloud

Every officer with a decent amount of time on the job knows the unexpected turns an investigation can take. Seeing a major case through to completion often involves giving up on a theory and taking your investigation in a different direction as new information becomes available. In How to Catch A Criminal, we look at the many ways not-so-perfect crimes are solved. This month, a very particular thief has a hard time letting his old habits die.

Often referred to as M.O., Modus Operandi is a major factor in creating a criminal profile. Identifying a common method in several cases can lead to a sole culprit. Generally, a criminal will keep the same tactics for as long as they work. If Law Enforcement begins to catch on, they will make the necessary adjustments to continue their crimes, or they'll be caught. The complexity of a criminal's M.O. is often what separates the amateurs from the successful career criminals. A low level street burglar is likely to kick in a door or break a window, take what they can, and run for the pawn shop. Typically this sort of crime spree is short-lived. In contrast, a skilled burglar, will scope out wealthy targets, determine the best time to strike, study the layout of the residence, take note of alarms and cameras, and take precautions to avoid leaving evidence behind once they make their move. In some instances, the M.O. is so specific to one very particular suspect, it alone is the giveaway that closes the case.

In 1991, the borough of Rumson, New Jersey, suffered a string of burglaries, all done in a very particular manner. The offender managed to enter the affluent homes without setting off alarms, waking the occupants, or even agitating family dogs. The only sign of entry was opened windows or carefully dismantled doors, preventing alarm sensors from tripping. Inside, the thief had the run of the place. They could make off with fine art, high-end electronics, cash, and any other valuables outside the sleeping homeowner's bedroom. Oddly, the only items missing were plates, forks, knives, teacups, and similar items, so long as they were silver. Searches near the burglarized homes would sometimes turn up a few of the cheaper stolen items, as well as certain chemicals in the soil. Such was the burglar's interest in silver, that he would bring a silver testing kit to ensure the stolen items were genuine sterling silver, and discard the less valuable silver plate items. This pattern of meticulous silver theft plagued the area, sometimes with multiple homes burglarized in one night. Increased police presence didn't deter the burglar either, as he snuck through neighborhoods unnoticed during overnight stakeouts and entered houses with officers parked outside on the street. The leads were scant, but one detective noticed similarities between the silver burglaries and others in a neighboring city from a few years prior, in which a wider range of items were stolen. An arrest had been made in those cases and the offender, Blane David Nordahl, was out again after early release.

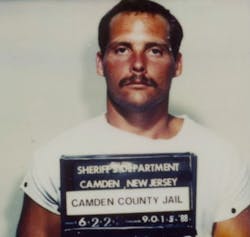

Later in 1991, the burglar struck again, ironically in the town of Little Silver, this time slipping up slightly. He climbed in through a window over the garden, and stepped onto the kitchen counter, leaving behind a perfect shoe-print thanks to the garden soil. Armed with their first piece of physical evidence in the burglaries, detectives obtained an arrest warrant for Blane Nordahl, with the hopes of obtaining a confession. Nordahl was located at a motel in Camden, New Jersey, and was arrested after a brief scuffle. Inside the motel were a pair of shoes that matched the print from the Little Silver case. This evidence combined with the offer of a plead deal was enough to get Nordahl to confess to more than three dozen burglaries in exchange for a five-year sentence, of which he served half before a good behavior release.

Blane Nordahl hadn't always planned on being a professional cat burglar. He was born in April of 1962, and moved from Minnesota to Wisconsin to New Mexico by the time he reached high school. After a difficult childhood and dropping out of school, Nordahl enlisted in the Navy. This briefly brought structure to his life, but a burglary arrest in 1983 resulted in the abrupt end to his military career. He continued to hone his new trade as a full-time burglar, pulling off small-time heists with a few accomplices. Being part of a crew just wasn't his bag though, because, simply put, nobody could match his capabilities. Nordahl was five foot four inches tall, lean, muscular, nimble, and quiet. All he needed was an small opening to crawl through and he could be in and out with plenty of goods to sell to a fence for a fraction of what they were worth. This led to Nordahl deciding to focus his efforts on only the most valuable items he could get his hands on. He began reading about rare antiques and studied how to identify the most high-end brands of silver, as well as how to differentiate sterling silver from silver plate. Nordahl was a fast learner and took care to learn from his mistakes. After serving time thanks to a muddy shoe-print, he elected to alter his methods slightly. From then on Nordahl discarded his clothes, shoes, and even his burglary tools after each caper. He also used different-sized shoes at times in order to throw detectives off his sent, just in case he left a trace.

By 1996 Blane Nordahl had expanded his operations outside of New Jersey, focusing on Greenwich, Connecticut, where he stole hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of silver. His Connecticut jobs included burglarizing the homes of Bruce Springsteen, Steven Speilberg, and Ivana Trump. The Trump burglary alone netted him 120 pairs of silver salt and pepper shakers. Lucrative indeed, but his “nothing but silver” style was becoming easily recognizable. A Greenwich detective heard about the similar New Jersey incidents, as well as cases being worked in East Hampton, New York. In short order, six Greenwich silver burglaries were pinned on Blane Nordahl. The attention this arrest garnered led Chicago detectives to name Nordahl as the prime suspect in 11 silver burglaries in a wealthy neighborhood. Due to Nordahl crossing between several states while committing his crimes, the FBI became involved, and soon, agencies from many states were calling in to report unsolved silver burglaries that looked like Nordahl's work. The cases weren't airtight however. Police suspected Nordahl was sending the silver by mail, to a fence who would send him cash in return. The lack of recovered items, combined with cash-only transactions, no DNA, and no fingerprints, meant these burglaries would be tricky to prove in a jury trial. In 1997, Blane Nordahl accepted a deal from prosecutors to plead guilty to conspiracy to transport stolen goods across state lines, and admit his involvement in over 140 burglaries in 15 states. He received a five-year sentence, and was paroled in 2001.

Just after his 2001 release, Nordahl got to work burglarizing lavish homes in Pennsylvania and back in his New Jersey stomping grounds until he was caught in Philadelphia in 2002 and arrested for violating his parole. Subsequently, he was released in 2003 and got right back in the game, nabbing silver across the eastern seaboard until, once again, he was arrested in Philadelphia. Sentenced to 8 years, Nordahl remained locked up until 2010. He moved to Florida and kept himself out of trouble until 2013, when he was charged with burglary and conspiracy. Each time Blane Nordahl was released from prison, there would be an epidemic of silver burglaries across the Eastern United States, carried out in his signature style. After his 2013 arrest, Nordahl was extradited to Georgia where he faced a first degree burglary charge. In 2017 he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, with enough cases pending in other states to potentially keep him locked up for life.

It is estimated Blane Nordahl made off with around $10 million in stolen silver during his cat burglary career. How much he actually made after fencing the items is unknown, but even a 10% profit of that is leaps and bounds more than any common criminal would make in a lifetime of thefts. Investigators had help from informants at times to help track him down, traced credit card transactions for rental cars and motel rooms booked in phony names, but the biggest factor in catching Nordahl over and over again was Nordahl's M.O. He put so much effort into becoming the world's foremost silver thief, no one else could even be considered a suspect.

About the Author

Brendan Rodela is a Deputy for the Lincoln County (NM) Sheriff's Office. He holds a degree in Criminal Justice and is a certified instructor with specialized training in Domestic Violence and Interactions with Persons with Mental Impairments.

About the Author

Officer Brendan Rodela, Contributing Editor

Brendan Rodela is a Sergeant for the Lincoln County (NM) Sheriff's Office. He holds a degree in Criminal Justice and is a certified instructor with specialized training in Domestic Violence and Interactions with Persons with Mental Impairments.